I’m involved to some extent in organizing a number of conferences whose CFP are open right now:

- Paul K. Feyerabend: A Centennial Celebration, the 12th Annual Values in Medicine, Science, and Technology Conference at the Center for Values in Medicine, Science, and Technology at UT Dallas (May 23-25, 2024). This conference focuses on the legacy of Feyerabend for contemporary history and philosophy of science, science & technology studies, science policy, and other relevant areas. 300-500 word abstract, Deadline: January 18, 2024.

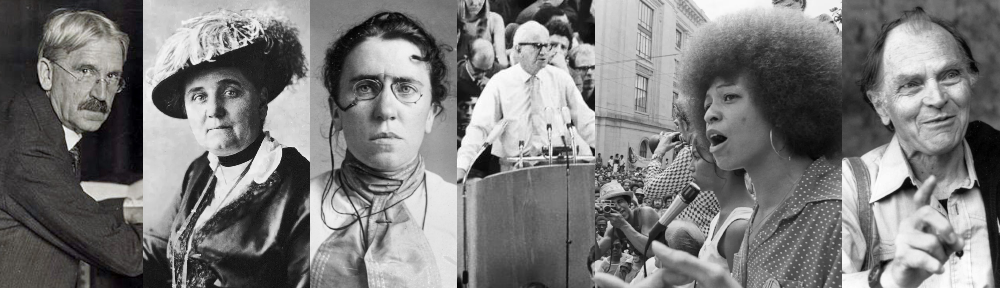

- John Dewey, Race, and Colonialism Workshop at the Center for Dewey Studies, Southern Illinois University (October 17-19, 2024). This workshop will bring together scholars working on the history of Dewey’s work on this subject in relation his contemporaries with scholars using Dewey as a resource for work on race, colonialism, and cultural pluralism. 5,000-6,000 word paper, Deadline: May 17, 2024.

- Popular Arts Conference in Atlanta, in concert with DragonCon (August 30 – Sept 2, 2024). This conference brings multidisciplinary scholarship in pop culture studies to a broad audience associated with the convention. Technically, the deadline has passed, but we are still accepting submissions at the moment, and anything submitted before the submission portal closes will be considered. ≤500 word abstracts for individual submissions, see instructions for group submissions.

Although I’m not involved this year, submissions are also open for the Philosophy of Science Association biennial meeting in New Orleans (November 14-17, 2024).

- Symposium Proposals, abstracts for panel and individual presentations (see instructions), Deadline: January 15, 2024.

- Contributed Papers, ≤4,500 word papers, Deadline: March 15, 2024